This song caught my ear when it popped up on my “Discover Weekly” Spotify playlist a while back. I liked it. Calming. Melodic. Nicely recorded. Performed with subtlety.

I thought it might be a good choice for a feature. But I also had questions: who was this Harrison Crabfeathers? What was his saga? And what about the pianist? He’s not the same recently-deceased Milos Forman who directed award-winning films, is he?

Following these questions quickly led me down a rabbit hole of mysterious characters, fake musicians, and Spotify conspiracy theories.

Part 1: Who was Harrison Crabfeathers?

The first mystery is in the song’s eye-catching title. “Harrison Crabfeathers” sounds either like a forgotten soldier from the American Civil War, or a bratty kid who met his unfortunate end in Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory.

It wasn’t hard to find references to the song – many musicians have covered it since Steve Kuhn composed it in 1972 – but I couldn’t find any insight into who the title character was. In all that had been written about the song, nobody mentioned the subject of the song beyond the fact that it’s a funny name.

What I did find is that the original version has lyrics, which are surprisingly short for a story that calls itself a saga:

Now and then I think of when his teeth were so small and white / He laughed when he heard the songs in the distant night / Later on his smile was gone, his lips spoke of silent things / The least he could do was more than his life could bring / Oh what a shame, what a terrible shame / To be lost and found below the ground, beneath every child that plays / His life was so short, it’s hard to believe today.

Yikes. Is this a song about a dead kid? Was Steve Kuhn telling us about the darkest moment in his life? Had he lost a younger sibling? A child? How had nobody written more about this?

Finally, after more digging, I found a reference to the song in an interview with Sheila Jordan, a jazz singer now in her 90s, from a book called Jazzwomen: Conversations with Twenty-One Musicians. According to Jordan, who knew Steve Kuhn well, the dead child theory was bogus, and the truth was much more mundane:

“Some people used to think [the song] was about a child who dies at an early age. Actually, it was originally named after a piano player who ws advertised in the back of a Down Beat magazine. Steve saw the name and liked it. He never knew the guy, but he was intrigued with his name.”

Hm. So Crabfeathers was probably a real person, but the songwriter never knew him or his saga; he was a muse in name only, a mysterious pianist who will probably never be tracked down.

I was disappointed. But I didn’t know that I was about to start chasing another mysterious pianist who will probably never be tracked down.

Part 2: Who is Milos Foreman?

Having heard several other versions of “The Saga of Harrison Crabfeathers,” I decided that I really did prefer the Milos Foreman version. It was slower, more laid back than most other versions out there. I also liked the quality of the recording; the warmth of the piano, the pianist’s gentle touch on the keyboard. I wanted to know more about Milos Foreman.

Googling “Milos Foreman” proved frustrating, because even with the slight variation in spelling, the famous director of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest took up pages and pages of results. Adding different search terms – jazz, musician, band, music – didn’t help much either.

It started to feel like this pianist, this other Milos Foreman, was a terrible self-promoter. Why did he go by this name if he knew that he wouldn’t show up in search results? On top of that, he seemed to have no web presence other than being on Spotify. No social media, no website, no tour dates, nothing.

But wait: his songs have millions of streams on Spotify. If he’s so invisible on the Internet, how is his music being streamed so much?

This was starting to feel suspicious.

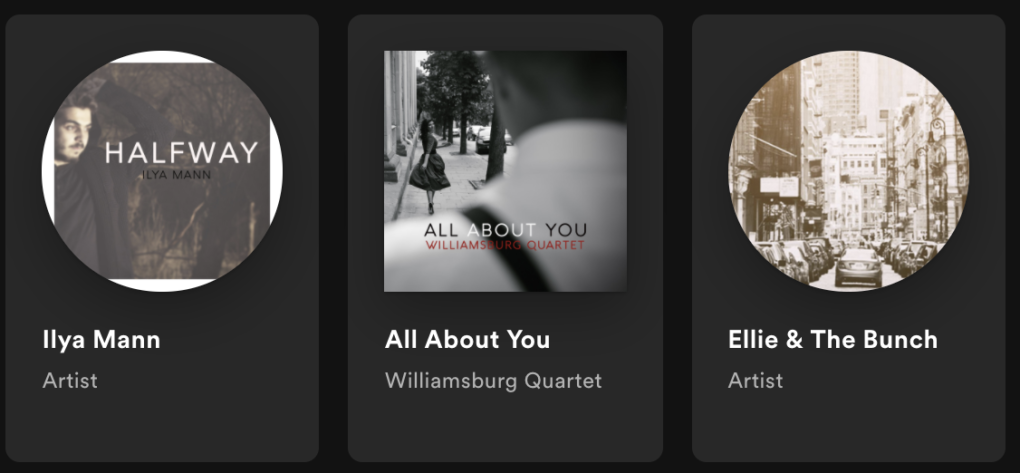

I then stumbled upon a Reddit post in which someone was asking if anyone had any information about a jazz group named Ellie & The Bunch. It was a puzzle similar to my own: the person had discovered a jazz act that played relaxed, beautiful music, but couldn’t find any web presence.

A response to the thread made an interesting suggestion:

“I have a theory that Ellie and the Bunch, Sassy Players, Williamsburg Quartet and Ilya Mann are all the same band as all their EPs were released on 18 March 2017, and they sound really similar to one another. But I have no idea who they are.”

I opened Spotify and looked up each of these bands in turn, and yes, they had each released EPs of only three songs on March 18th, 2017, with stream totals in the millions. And yes, they all did sound very similar. More importantly, they sounded very familiar.

I had a weird thought, accompanied by a weird feeling.

I went back to the information on Spotify for Milos Foreman, and the album, Jazz Standards, from which “The Saga of Harrison Crabfeathers” was taken. I checked the album’s release date: March 18, 2017.

What was going on here?

Part 3: Spotify and “Fake” Musicians

As much as I wanted to feel like I was uncovering something, I took a step back and told myself that I cannot be the first person to have noticed this.

Sure enough, fishiness of this kind has been discussed in recent years by everyone from intense YouTubers to Rolling Stone. The basic idea, as outlined in the Rolling Stone article is this:

- Some music production companies, like Epidemic Sound in Sweden, create generic ambient music and sounds (falling rain, nature sounds etc.) and then submit them to Spotify in bulk, at a lower royalty rate than “normal” artists would.

- These tracks get tons of plays, because Spotify fills up their “sleep” and “ambient” playlists with these tracks. Spotify does this because they, understandably, enjoy paying the lower royalty rates.

- Big distributors like Sony and Universal got peeved at this, because they saw it as Spotify giving more plays to those music production houses.

- According to Rolling Stone, those same distributors have stopped complaining and started basically doing the same thing themselves: creating generic, wide-appeal music using in-house musicians, and then creating “fake” bands through which they release the music.

- This means they get more songs on more playlists, and because the big labels have already paid the session musicians, the labels can keep all the money.

So what this likely means is that Milos Foreman, Ellie & The Bunch, Williamsburg Quartet, Ilya Mann, and potentially many others are all the same band. Their songs – usually instrumental jazz standards with a soothing, background-jazz kind of vibe – were taken from the same recording session and divided up amongst their respective make-believe band names.

I can’t say for sure that’s what’s going on, but it seems to be the most likely explanation. I mean, listen to this track and this track and tell me that’s not the same group of musicians.

Coming to this conclusion, I felt pretty pleased with myself. I briefly imagined myself quitting my job and starting up as a freelance investigative journalist. That satisfaction came to a crashing halt a few seconds later, when I suddenly realized that I had been taken in by what felt a bit like a giant music industry scam. My ears had latched onto this song by this non-existent artist. “Ooh, that’s nice,” I had thought to myself, “I should feature that on the blog.”

Is my taste in music so predictable that I was duped by generic, corporately-produced dinner jazz? Am I the prototype for the music fan of tomorrow, who gets a weekly serving of AI-enhanced tracks, algorithmically optimized for mass appeal?

No. And also yes…but also no.

Part 4: Lessons and Rationalizations

If I’ve learned anything from this, it’s that I need to be careful about putting my trust in the gods of algorithm. More to the point, if my purpose with this blog is (at least in part) to find and support new artists, I need to make sure that those new artists are real and worthy of support.

But at the same time, this “Harrison Crabfeathers” song that I heard and liked, it is performed by real people. That’s a real pianist I’m listening to, even if their name is not Milos Foreman. And even if they’re not seeing any royalties for this, I want them to know that I really do like this song. Of all the versions of “Harrison Crabfreathers” that I’ve heard, this is easily my favourite. Whoever played it played it well.

So, Milos Foreman, whoever you really are, thank you. Pass on my best wishes to your fellow session musicians.

And as for you, Mr. Crabfeathers, thank you as well. After all, you were the original inspiration for this song, even though you probably never knew it, and even though you probably never had a saga worth writing about.

The saga, in the end, wasn’t Harrison Crabfeathers’ saga at all; it was mine. It was a weird journey through jazz history, the modern music industry, and my own existential crisis as a music fan.

What makes this a beautiful song:

1. The best piano playing I’ve heard since Ellie & The Bunch.

2. The best upright bass I’ve heard since the Williamsburg Quartet.

3. The best brushed drums I’ve heard since Ilya Mann.

Recommended listening activity:

Designing the letterhead for your new Private Investigation business.